This is the fifteenth installment of a series documenting an ordinary New Yorker attempting to exercise his Second Amendment rights: Part I (license application), Part II (application rejected), Part III (the lawsuit), Part IV (appeal filed), Part V (appellate briefing complete), Part VI (N.Y. Appeals Court Not Interested in Ending NYPD Corruption), Part VII (Corruption? You Can’t Prove It!), Part VIII (appeal to N.Y. high court), Part IX (N.Y. Court of Appeals won’t hear), Part X (Federal Lawsuit Filed), Part XI (Federal Court Refuses Challenge), Part XII (U.S. Court of Appeals), Part XIII (No Help from Second Circuit), Part XIV (Supreme Court Strikes Down Proper Cause).

Total Time Spent So Far: 142 hours

Total Money Spent So Far: $4,102

It’s been more than a year since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down New York’s corrupt “proper cause” requirement, wherein only those whom the licensing officers deemed had a “good reason” to exercise their constitutional right to bear arms were permitted to do so. In anticipation of the ruling, I filed a new application a couple months before the ruling, so in theory, I should have my license by now, right?

Of course not.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision, N.Y. Gov. Kathy Hochul crammed through legislation called the Concealed Carry Improvement Act. In addition to futility, such as declaring Times Square to be a gun-free zone (seems criminals didn’t get the memo), CCIA was designed to make it as difficult as possible to obtain a license. To that effect, it contains three particularly unconstitutional requirements: 1) mandatory disclosure of all social media accounts used in the last three years, 2) four letters of recommendation from others, and 3) 18 hours of training.

The social media requirement is particularly odious: it stands no chance of helping to keep guns from dangerous people, because dangerous people will simply not disclose the social media accounts they use to express their dangerous views. Sure, a licensing officer might find that account anyway, but that was already possible without CCIA. On the flip side, now if you have an OnlyFans, you’re required to let the police look at your body before you can exercise your rights, just as those who may anonymously use social media to discuss medical issues, their sexual orientation, or their fetish preferences must bare themselves to the police department.

The other two requirements fare no better: reference letters require outing one’s self as a (future) gun owner in a city where doing so is, in many scenes, socially unpopular, and re-introduces the same sort of “approval of others to use your rights” requirement the Supreme Court just struck down. And the training requirement serves no purpose other than to discourage applicants: it is the longest training regimen of any state, and there simply is not 18 hours worth of conversation to be had about responsible gun ownership — explaining when deadly force is legal, safe gun storage, and the like simply does not require more than a few hours. I support reasonable pre-licensure training to ensure that everyone who owns a gun understands their responsibilities, but that’s clearly not the intent or effect here.

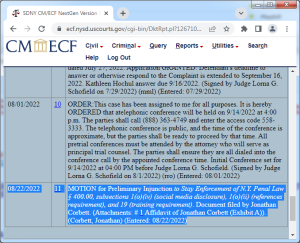

So, I challenged these three requirements in U.S. District Court last July, and U.S. District Judge Lorna Schofield denied my request to enjoin all three of them. As to the first two, the state argued that they would not apply them to those who applied before CCIA took effect, and therefore I had no standing. Of course, I would be required to follow those requirements on license renewal, but that happening, she ruled, was too far away. That said, at least I have a commitment that my application will be processed without these requirements… for now.

As to the training requirement, the standard set by the Supreme Court for when a gun restriction is lawful is that there must be a tradition of similar laws at the time the Second Amendment was written; a so-called “historical analog.” Obviously, gun licenses didn’t exist at the time, and so the state argued that since militia membership was required, and militia membership required gun training, that this is “analogous” to CCIA’s training requirement.

I’ve appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, explaining why this is nonsense:

“First, as the government concedes, mandatory militia membership requirements applied only to 1) able-bodied, 2) male, 3) citizens of the state, 4) within a certain age range. … People who were disabled or otherwise not physically able to serve in the militia were not prohibited from carrying concealed weapons or required to partake in supplemental training. Neither were women, nor were those outside of the 30-year age range where service was expected, nor were those who lived in a state without being a citizen thereof. These “exceptions” entirely swallow the analogy, as more than half the population is female and a substantial percentage of the remaining male population would have been physically unfit to serve, a non-citizen, or of an excluded age.”

Beyond that, militia gun training serves the opposite purpose — teaching how to kill people with guns rather than educating to prevent gun deaths — and was entirely unconnected to gun ownership (that is, failure to participate in the militia did not result in disenfranchisement of gun rights). It is simply not an analogous restriction on gun rights.

My appeal is now fully briefed and likely to be scheduled for oral arguments in the fall. In the meantime, the NYPD is slow-walking all license applications, and mine has not even been scheduled for an interview by this time, now 15 months later. Although the tide is turning, at this time, it is still impossible to get a gun license in New York City.

Corbett v. Hochul – Appellant’s Brief (.pdf)

Corbett v. Hochul – Appellee’s Brief (NYC) (.pdf)

Corbett v. Hochul – Appellee’s Brief (NYS) (.pdf)

Corbett v. Hochul – Reply Brief (.pdf)

Electric Zoo is a large annual electronic dance music festival held on Randall’s Island in Manhattan. They are no stranger to legal issues, and in fact my firm had

Electric Zoo is a large annual electronic dance music festival held on Randall’s Island in Manhattan. They are no stranger to legal issues, and in fact my firm had

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He

On July 11th, 2022, I

On July 11th, 2022, I

Only 50 years ago, there were places in this country where you could not buy non-essential items on Sundays, because it was a crime for shopkeepers to sell them to you.

Only 50 years ago, there were places in this country where you could not buy non-essential items on Sundays, because it was a crime for shopkeepers to sell them to you.